Could the energy crisis derail our transition to net-zero?

20 October 2021 Climate ChangeSustainability

If you have been following the news for the past couple of weeks, the term “energy crisis” has been hard to miss. Across the world, shortages in energy sources are wielding havoc. In Europe, natural gas prices are on the rise, oil prices are going up, and China is struggling with dwindling coal reserves. And as the world is pushing towards a transition to low-carbon economies, could this spike in fossil fuel prices challenge the post-COVID 19 green economic recovery?

What exactly is leading to these high energy prices?

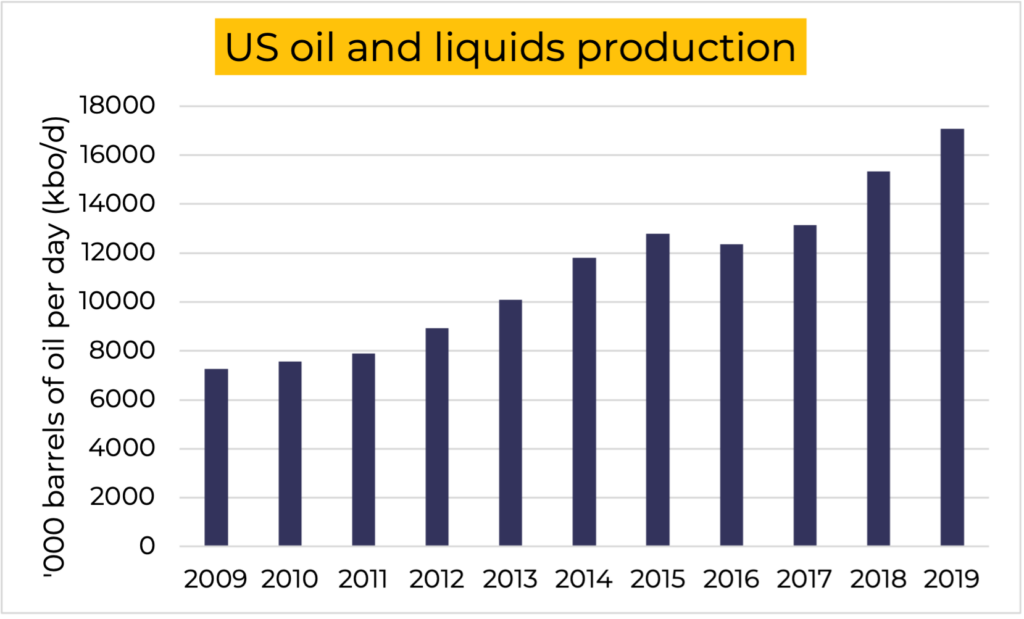

Energy prices have been formed through many past cycles by supply and demand. Over the past few years, we have seen a confluence of factors which enabled the supply of more, and cheaper energy. Strong oil supply growth in the US (8.9% a year between 2009 and 2019, see below) followed by an oil price war between OPEC and Russia that resulted in an oversupplied oil market, and the sharp decline in costs of renewables (at parity with fossil fuels when it relates to power generation) kept overall energy costs low for consumers and businesses. That was before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Strong oil supply growth and fast-declining renewable costs

Source: EIA, IRENA, Clim8Invest computations; NB: Liquids = Oil + NGLs; CSP = Concentrated Solar Power

In the first half of 2020, COVID-19 first created a demand shock (energy consumption was down 4.5% in 2020), notably for oil (mobility was significantly curtailed in 2020), requiring a coordinated answer from OPEC+ which is still in force, in practice, to adjust supply with demand. To address the economic shock (demand and supply), global central banks injected a lot of liquidity into the financial systems which had two consequences: boosting economic growth in 2021 which lead to higher energy demand, and favouring inflows into commodity markets. The combination of the two are the main drivers behind the recent spike in fossil energy prices.

Put simply, energy demand is rising (from a depressed base) but oil & gas producers haven’t responded to price signals yet (they are reluctant to boost investment in order to increase supply). In our view this is driven by three main reasons:

- Balance sheets – oil and gas producers have not yet fully repaired their balance sheet capacity vs. pre-pandemic levels1

- US Shale is not the oil machine it used to be – growth potential has been impaired and Saudi/Russia now in control of the oil market.

- Energy transition – listed oil and gas players are under significant pressure from their shareholders not to increase investments in legacy fossil fuels activities.

2020 was a record year in terms of installation, resulting in a 10% YoY growth in renewables capacity (wind and solar). Yet, this pace of growth is proving itself as too slow to make our economies less reliant on fossil fuels. And while most of the recent fiscal packages (EU Green Deal, US Infrastructure Bill, China’s 2060 vision) support the introduction of renewable energy, we believe the velocity of money remains too slow to reach net zero by 2050. According to the IEA World Energy Outlook 2021, fiscal measures dedicated to the green recovery amount to $2.7tn, o/w $0.4tn directly dedicated to clean energy. Indeed, in the IEA’s net zero scenario, electricity production from solar and wind should grow at an annual pace of 21% and 17% to 2030, dropping to 11% and 10% between 2030 and 2050. A quick catch up is absolutely necessary to keep us aligned with 1.5°C.

Despite the competitiveness of renewable energy against fossil fuels, our economies remain heavily reliant on fossil fuels as they still account for 83% of the world’s primary energy consumption (coal included), and 94% of CO2 emissions (coal included) in 2019, a picture that is by and large no longer accepted by our societies.

The prices of oil and gas have significantly increased over the past twelve months (see charts below), implying that energy bills for households and businesses will start to be noticed over the next few quarters.

Source: FactSet, Clim8

Put together, the lack of response by energy producers, the seemingly slow rate of growth in the expansion of renewable capacities and the underinvestment in the broader energy landscape might be leading us into a short term future of more frequent shortages and price volatility.

Energy transition vs. security of supply

As economies grow, so does energy demand (and vice-versa). In practice this means that producing goods and services (economic output), requires energy to fuel production, whether it be manufacturing plants or computers. An increase in output usually means an increase in energy demand. Thus, having access to abundant and cheap energy is in many ways necessary to creating wealth.

GDP growth vs. primary energy consumption

Source: BP statistical review of the world, IMF, Clim8.

Our societies are increasingly keen to see the green transition happen. Equally, facing energy shortages is not acceptable in 2021. Anecdotes of empty gas stations in the UK, or Chinese plants forced to shut down because of very low coal inventories are flourishing and provide evidence that we’re entering an uncertain energy outlook, at least in the short term. This complex equation – short-term security of energy supply vs. long-term decarbonisation – can be solved in multiple ways. As an example, China recently approved the increase in domestic coal production and started to re-import Australian coal (despite a ban) to prevent electricity prices from skyrocketing further. Yet, accelerating the energy transition requires in itself energy. It is worth mentioning that the IMF slightly reduced its 2021 GDP growth forecast to 5.9% (from 6%), with fuel prices inflation being one of the drivers of this revision.

Can the energy crisis dent the green transition?

Over the past decade, economies of scale, better efficiency (i.e. ability to convert sun radiation or wind resource into electricity) and cheaper cost of capital were the main drivers behind bringing the cost of renewables down. However, there was very little inflation associated with it in the past. These days, inflation is front and centre of the economic agenda, with energy possibly the most visible example of inflation impacting our economies. But it’s just not energy. For instance, copper prices have jumped by 82 percent 2 over the past two years, semiconductor shortages are in the news, wage inflation is becoming apparent in selected regions, and polysilicon prices are on the rise (polysilicon is a key component of solar modules). We believe this could create near-term headwinds on the penetration of renewable electricity:

- The ability to increase production capacity for wind and solar due to widespread shortages and/or higher costs

- Economic rationale to switch to renewables, potentially more challenged in the absence of a global CO2 price and/or coercitive mechanisms

- Increased cautiousness from consumers (households and corporations alike) that may prioritise in the short term other spending categories to navigate this more uncertain environment

Conversely, there are enough historical references that support the view that high oil & gas prices lead to renewed investments in alternative energy sources (nuclear acceleration in the wake of the 1973-75 oil shock such as in France, hydrogen as we headed into the dotcom bubble of 2000, solar in 2007-08). We believe this time will be no different, especially given the widespread policy and societal support for clean energy with net-zero pledges flourishing.

All put together, the sharp decline in renewable costs can be challenged in the near-term by supply chain inflation (energy costs being one of the many factors at play) but there are many reasons to believe that current market forces and the push to decarbonise quickly the energy system will be able to shrug off these headwinds.

Conclusion

There is little doubt about the direction of travel. More renewables (wind and solar) and alternative fuels (biofuels from waste residues, hydrogen) are required at a massive scale in order to reach the net zero emissions goal by 2050. Renewables can now compete with fossil fuels on price as costs have been sharply decreasing over the past decade. And yet, we might be entering a period of less abundant, more expensive energy prices, still due to our large reliance on fossil fuels. Despite inflation building in supply chains and raw materials, this is an opportunity to accelerate the energy revolution that requires more energy, and a much cleaner energy, to drive sustainable global economic growth. This has a cost: $4Tn of annual investments to 2030 according to the IEA net zero scenario. But the cost of inaction in the long term is, we believe, far greater than that.

References

1: analysis based on FactSet data for the FactSet industry group World Minerals; net debt to EBITDA at 1.5x as of Q2 2021 vs. 1.2x as of Q4 2019; total debt/total equity at 61.7% vs. 51.1%

2: source FactSet, as of October 19th, 2021.

0 Comments